|

||

|

||

(C)2001 Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. No reproduction or republication without written permission.

掲載のテキスト・写真・イラストなど、全てのコンテンツの無断複製・転載を禁じます。

|

||||||

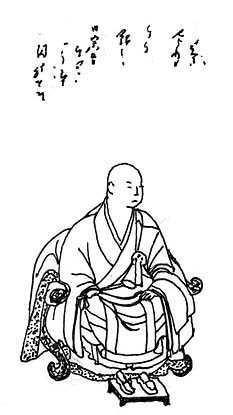

| chinsou 頂相 | ||||||

| KEY WORD : art history / paintings | ||||||

| Also chinzou. Lit. head's appearance. A naturalistic portrait, sculpted or painted, of a Zen 禅 master's head. Chinsou can be divided into two types depending on their function. First are inka 印可, given by a master to his disciple as a certificate of the student's attainment of spiritual awareness and as a symbol of the clear and unbroken lineage of a sect. These portraits often include hougo 法語, or words of religious enlightenment, inscribed by the priest depicted. A portrait done in a realistic and detailed style, together with an inscription, provided the disciple with both the tangible presence and the inspiration of the teaching of his master long after personal relations were severed through parting or death. Second are keshin 掛真 which were to be hung or placed together with imaginary portraits of Zen patriarchs *zenshuu soshizou 禅宗祖師像 in either the dharma hall *hattou 法堂, or main gate *sanmon 三門, of Zen sect temples in connection with memorial services. Chinsou of this second type were made after the master's death and the inscription was usually added by a close contemporary. Chinsou sculpture belongs entirely to the keshin category. The desire to symbolize the personal relationship between sitter and disciple recipient, or to memorialize a master for later followers, necessitated a high degree of verisimilitude. Moreover, the chinsou artist was encouraged to go beyond the mere physical likeness to capture something of the inner spirit of his subject. Painted chinsou are known in three formats. The most orthodox type show the priest wearing his full robe *noue 衲衣 and surplice *kesa 袈裟, seated en face in a large upholstered wooden armchair *kyokuroku 曲ろく, holding a bamboo baton shippei 竹箆 or whip kyousaku 警策 in the right hand. He is often shown with legs tucked under and shoes on a small footrest kutsudoko 沓床. A second format which evolved later was the half-length or bust portrait hanshinzou 半身像 that focuses on the individualistic details of the face. Typically in such depictions, even the hands of the priest will be hidden beneath the voluminous sleeves except for the exposed thumb of the left-hand. Orthodox painted chinsou feature a naturalistic style with fine linear details and a full range of colors, although some later examples are rendered more simply in ink monochrome. The third category may be termed special formats, including portraits of a master walking or resting *kinhinzou 経行像 and usually including landscape elements, as well as bust portraits in a circular framework *ensouzou 円相像. The chinsou tradition is said to have begun in China, possibly initiated by the needs of Japanese students. In the late 12c when Japanese priests returned from study in China, they often brought chinsou of their Chinese masters. A representative early example is the anonymous 1238 portrait of Bujun Shiban 無準師範 (Alt. reading Mujun Shihan, Ch: Wuqun Shifan) presented to the Japanese priest Bennen Enni 弁円円爾 (Shouitsu Kokushi 聖一国師; 1202-80), who on his return founded Toufukuji 東福寺. Initially Japanese Zen temples lacked the artists to produce chinsou and therefore employed portrait specialists from other sects. A good example is the 1265 portrait of Gottan Funei 兀庵普寧 (Ch: Wuan Puning; 1197-1276) by Takuma Chouga 託磨長賀, priest-painter of the esoteric temple Shoudenji 正伝寺. Early chinsou are unsigned, a fact that has greatly complicated the issue of determining the artist and even country of origin. Perhaps the earliest signed chinsou by a Japanese painter priest of a Zen sect is the portrait of Muhon Kakushin 無本覚心 by Kakue 覚恵 in Koukokuji 興国寺. By the mid 14c, Japanese artists were producing high quality chinsou as demonstrated by the anonymous 1334 portrait of Daitou Kokushi 大燈国師 (1282-1338) in Daitokuji 大徳寺 and the 1349 portrait of Musou Kokushi 夢窓国師 (1276-1351) by his disciple Mutou Shuui 無等周位 in Myouchi-in 妙智院. From the late 14c painter-priests such as Minchou 明兆 (1351-1431) produced large numbers of excellent chinsou at the ateliers of major Zen temples. The creative vigor of the chinsou tradition continued in the 15c, exemplified by the remarkable portrait of *Ikkyuu 一休 (1394-1481) in Daitokuji 大徳寺, attributed to his disciple Bokusai 墨斎 (?-1492). Chinsou were produced throughout the Edo period, with the portraits of the Oubaku 黄檗 (Ch: Huanglo) sect of special note. | ||||||

|

||||||

| REFERENCES: | ||||||

| EXTERNAL LINKS: | ||||||

| NOTES: | ||||||

(C)2001 Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. No reproduction or republication without written permission. 掲載のテキスト・写真・イラストなど、全てのコンテンツの無断複製・転載を禁じます。 |

||||||